Art Powell's Pioneering Impact on Football and Society

Art Powell: Why he belongs in the Hall of Fame

An in-depth look at pro football's Inconvenient Truth

Art Powell was a tough man who didn’t suffer fools or condone inequities. He was one of nine siblings in a legendary San Diego sports family, literally the genesis of his athletic greatness.

This week, a half century after he first became eligible and 55 years after his last game, Art Powell was named as a finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame's 2024 Class. But his back story began the year he was born in 1937 just before his family moved from Dallas to San Diego.

Athletic greatness was a family tradition

His father, Elvin, at about 6-3, 220, was insanely athletic. He was a tennis champion, scratch golfer, a standout in the Negro baseball league and toured with Satchel Paige's barnstorming team. As a black man, Elvin was unable to participate in major sports leagues or events in Texas. So, under pressure from the KKK seizing his land, he moved his growing family from Dallas to San Diego. Elvin emphasized that his children should never accept segregation.

His point was well taken, evidenced by generations of social activism by his descendants, including Art who famously boycotted four pro football games while establishing himself as one of the best wide receivers in history.

Oldest brother Charlie earned 12 letters in five sports at San Diego High. He signed with the St. Louis Browns at 17 years old (played with minor league Stockton Ports) but after showing his power as a batter teams pitched around him and he become bored. He considered an offer from the Harlem Globetrotters, but opted to signe with the San Francisco 49ers at 19, the youngest player in NFL history.

As a rookie, Charlie Powell sacked Detroit quarterback Bobby Layne 10 times in one game, then they went drinking together late into the night. Charlie eventually moved full time into his favorite sport, boxing. He became the No. 5 ranked heavyweight boxer, with wins over big name fighters and a loss to a guy named Cassius Clay, three fights before Clay became Muhammad Ali and beat Sonny Liston for the World Heavyweight Championship

Art's brothers also included multisport stars Ellworth and Jerry, meaning he probably faced his toughest competition before leaving home. So it should have been no surprise when he became one of the most prolific wide receivers in pro football history after ten years with the Philadelphia Eagles, New York Titans (Jets), Oakland Raiders, Buffalo Bills and Minnesota Vikings.

Powell's pro football numbers support HOF inclusion

By the time a knee injury forced him to retire in 1968, Powell had seared his name in pro football history with marks that still stand 55 years since his last game, such as:

● No. 2 in touchdowns per game (.77), behind only Don Hutson (.85)

● No. 4 in frequency of touchdowns (one every 5.9 catches), behind only Don Hutson (4.92), Paul Warfield (5.03), Tommy McDonald (5.89)

● No. 8 in yards receiving per game (76.6), with all seven ahead of him playing in this century, long after rules were imposed to restrict defenders from mugging receivers, starting with the 1978 edict to limit such contact to within five yards of the line of scrimmage.

As one of the most explosive receivers of his era, Powell caught 479 passes for 8,046 yards and 81 touchdowns in 105 games at wide receiver. He ranked third in AFL history in receiving yards, behind only Hall of Famers Lance Alworth and Don Maynard and posted five seasons with 1,000 yards receiving and two more above 800.

In his seven full seasons before blowing out a knee, Powell averaged 65 catches for almost 1,100 yards and 11 touchdowns a season. And those were 14-game seasons with legalized mugging on wide receivers.

Yet it wasn't until this year that Powell progressed far enough to be discussed by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Seniors Selection Committee — a half century since becoming eligible and eight years after he passed. He survived a cutdown from 12 semifinalists to three finalists. The other two are linebacker Randy Gradishar, from the Denver Broncos' Orange Crush defense of the 1970s, and lineman Steve McMichael, a tackle in the Chicago Bears' stifling defense of the mid-1980s.

The Hall of Fame's full, 50-person selection committee will finalize their fate during a January meeting. Each Seniors semifinalist needs 80 percent "yes" votes to be inducted.

"They screwed him"

Why did it take so long for Powell to be discussed? Let's take a deep dive into his incredible career and see if there is an explanation.

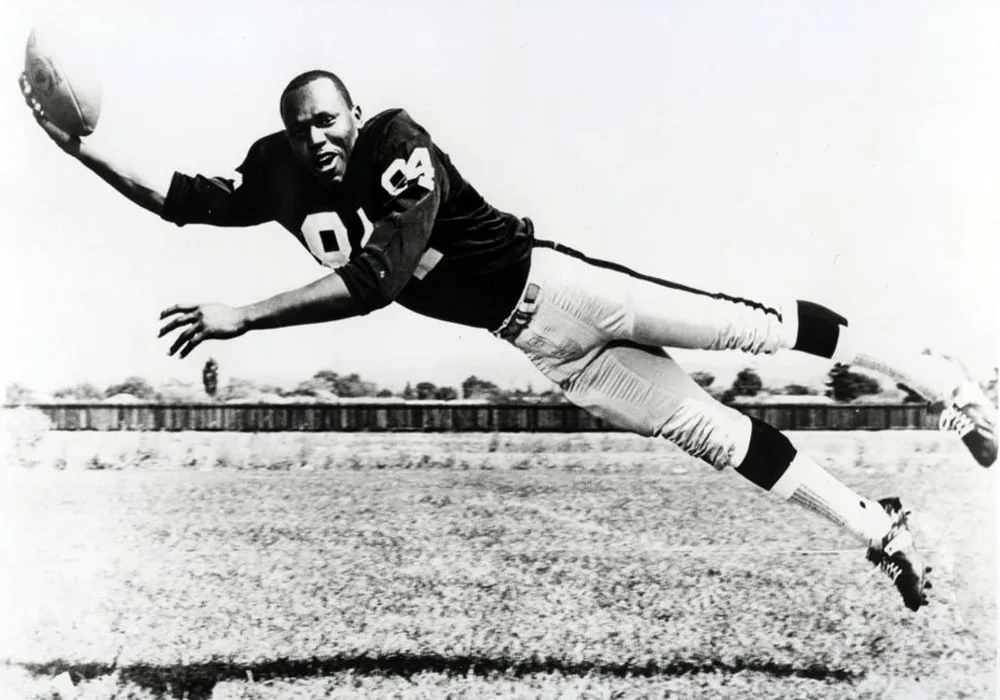

At about 6-3, 212 pounds with a track sprinter's speed, Powell was ahead of his time as an unstoppable force on the field, especially going deep.

"It's not enough to have lots of catches and lots of yards," Powell said. "I want lots of touchdowns. That is the goal, right?"

"He was a quiet man whose actions spoke volumes," said former All-Pro cornerback Fred "Hammer" Williamson. "He was feared. If he played with these current hands-off rules...oh my gosh, Powell would dominate. He was not someone you trifled with on or off the field."

On the field, Powell's althleticism was a thing of beauty, unless you were a defensive back.

His impatient ascent in sports was dazzling at every level. At San Diego High he starred in basketball, track, baseball and, of course, football. After a brief stop at San Diego City College, where he scored 50 points in one basketball game, Powell was lured to San Jose State. He led the nation with 40 receptions in football and in basketball attracted attention from the Globetrotters, à la brother Charlie. He opted to play for pay in the Canadian Football League.

Still 19 years old, Powell signed with the Toronto Argonauts in 1957 and split 10 games between the Argos and Montreal Alouettes, catching 33 passes for 628 yards — more than 19 yards a grab — with three touchdowns, two interceptions and a few kickoff and punt returns.

Finally eligible for the NFL's Draft held in December 1958-January 1959, Powell wanted to get away from playing 60 minutes per game in the CFL. He was drafted by the NFL's Philadelphia Eagles, ostensibly as a wide receiver, and signed a contract laden with incentives for catching passes.

Powell didn't collect a penny of incentive money despite a dazzling rookie season. The Eagles never played him on offense. He was relegated to backup safety and kick returner. He made the best of it with three interceptions, two fumble recoveries and finished No. 2 in the NFL on kick returns, including one for 95 yards.

“They screwed him,” recalled John Madden. The future Hall of Fame coach was an Eagles rookie teammate with Powell and talked about him several times during our annual bus rides to the Indianapolis Combine when the subject inevitably turned to Powell not being in the Hall of Fame.

“They had him returning kicks and punts and playing defense, so there was no way he earned a penny of that incentive money as a receiver,” Madden said. “But he was one hell of an athlete, a big tough guy who could do a lot of things. So he was second in the league in returns and made some big interceptions. He was really something.”

Powell's relationship with the Eagles worsened when he refused to play in a 1960 preseason game against the Washington Redskins in Norfolk, Va. It would be the first of four times Powell boycotted a pro football game because of segregation, an action that in those days was unpopular and frowned upon in most parts of the country.

He learned the Eagles' Black players could not stay in the team hotel with their white teammates. Although several players initially said they would join him in a boycott, Powell stood alone when the time came. He took heat from the media and fans — and the Eagles cut him. He late acknowledged that he was blackballed in the NFL.

Enter the more progressive AFL, in its first season, and New York Titans coach Slingin’ Sammy Baugh, a Hall of Fame quarterback who knew a wide receiver when he saw one. Powell was signed immediately, lined up at wide receiver within days of being cut by the Eagles and caught four touchdowns against the Buffalo Bills.

In 1960, Powell caught 69 passes for 1,167 yards and led the league with 14 touchdown catches, an average of one a game. This was the first time in football history that two teammates, Powell and Don Maynard, each gained 1,000 yards receiving. After they did it again in 1962, the Titans’ financially troubled owner Harry Wismer tried to cash in, thinking he could auction Powell to the highest bidder.

Powell thought otherwise, knowing he played out his contract, and went home to Toronto and his wife Betty, his most significant reward for time spent in the CFL. The Bills actually coaxed Powell into signing a contract but the team didn't submit it to the league because they were concerned it would cost them compensatioon. There was plenty of confusion about his status amidst Wismer's disgraceful conduct with a bogus auction in New York.

Al Davis was happy to clear up the confusion. After being hired in late December, 1962, as the Oakland Raiders' 33-year-old rookie head coach, Davis flew to Toronto, dined with Art and Betty. He told Powell how the wide receiver would flourish in a passing attack that featured him. Davis returned home by New Years with Powell's player contract. Oh, and he submitted it to the league. Considered a bold and even bombastic move at the time, this signing was mere hint of future moves by Davis.

That season quarterback Tom Flores returned from a year away with tuberculosis and teamed with Powell to lead the Raiders — and that still little-known rookie head coach — to a 10-4 record. Following the 1-13 finish in 1962, the 1963 Raiders season became the biggest turnaround in American professional team sports history. Powell led the league with 1,304 yards receiving and 16 touchdowns, as the Raiders were No. 1 with 31 touchdown passes. Again, these were 14-game seasons.

Spin forward to 2006 and Davis, by then a Hall of Famer himself, fondly recalled his season as a rookie head coach with Powell.

"I wish I could take you all back to 1963," Davis said. "I had one of the greatest players who has ever played this game and he was tough to handle. He was the T.O. of his time. And he was great. His first year for me he carried us. He caught 16 touchdowns. His name was Art Powell. The difference between Powell and T.O. was that Powell took a stand for a cause."

In 2004, Powell recalled Davis with fond appreciation.

"Al Davis knew about my stand on social matters," Powell said. "He knew I was against segregation. He knew I boycotted games. He knew I lived in Canada because as a mixed-race couple it was more comfortable than living in the States. He knew all of it. It wasn't that he didn't care. He cared, understood and agreed. He would later prove that when challenges arose and he stood up and did what was right."

Powell's commitment to social justice

The first challenge was an Aug. 23, 1963 preseason game against Powell's former team, renamed the Jets, in Mobile, Alabama's Ladd Memorial Stadium.

"We weren’t going to stay together as a team,” Powell said. “They were going to rope off a section for the Colored fans to sit in, and the Colored fans wouldn’t be able to use the bathroom. So this was my first big challenge with Al Davis, but it turned out it wasn’t a challenge at all.”

After meeting with Powell and teammates Bo Roberson, Clem Daniels and Fred Williamson, Davis moved the game to Oakland.

"Al never put another game in the South during the time I was with the Raiders," Powell said.

In January of 1965 the AFL All-Star game was scheduled for New Orleans.

"We can't get a cab from the airport," said Powell. "We're told we have to call for a Colored cab." There were numerous other issues. A bouncer told one Black player that if he entered the bar he would be shot. Killed.

"There were 22 Black athletes all together on the two all-star teams," Powell said. "Before I know it they are all at our hotel and it must be three or four in the morning. And we have a meeting.”

They decide to leave the city. Powell was mindful of being burned in Philadelphia by teammates who reneged on plans to boycott, leaving him alone in the act. He drew up a simple list signed by all 22 players, saying they intended to boycott. And they all left town. By the time Powell landed in New York, on a layover to Toronto, the game had been moved to Houston, thanks to Davis and several team owners.

Despite his great relationship with Davis, Powell asked to be traded closer to Toronto after the 1966 season, saying he wanted to be near business interests. Davis didn’t want to trade Powell, but later confided that he thought Art believed Betty would be more comfortable living back in her hometown Toronto. That is where they were wed in 1957, believing mixed-race marriages were illegal in the U.S., which was true in many states. And that is where Betty's family lived.

The Raiders traded Flores and Powell to Buffalo in exchange for quarterback Darryl Lamonica. Art later wished he stayed with the Raiders but moved with Betty to Toronto and commuted to Buffalo in 1967. Lamonica led Oakland to Super Bowl II, a loss to the Green Bay Packers. Powell, whose career realistically ended that season with a knee injury, agonized watching the SBII loss in the stands.

"I just know we would have won if I stayed in Oakland," he said. Powell attempted to play with Minnesota in 1968, but couldn’t overcome the knee injury and retired, ending one of the greatest careers by a wide receiver in pro football history.

"Art Powell's career is an important chapter in pro football history," said Hall of Fame coach Bill Wash, who was a fellow San Jose State alum and a coach with the Raiders in 1966, before creating a dynasty with the San Francisco 49ers.

“As a player he was far before his time. He would have been a sensation in any era. Art was his own man and fiercely independent. He was not afraid to voice his opinions and to take a stand.”

"Art was way ahead of his time in a lot of ways," Flores said years later after coaching the Raiders to two Super Bowl wins and being inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame himself. Flores knew Powell both as a college cornerback and as the Raiders quarterback who threw most of the great receiver's pro touchdowns.

"He was hard to cover before the catch and even harder to tackle after. He was a difference-maker,” said Flores, himself a pioneering minority in pro football. "You must have people to speak out and not just speak up, but they have to be active. They have to walk the walk and talk the talk. Lip service is cheap. Nowadays players have the platform and the microphone and they need to keep using it and using it wisely. That's what Powell did."

But Powell's actions during a historic time of social upheaval in the country impacted his legacy and often overshadowed his standing as one of the elite wide receivers in the game. He was shunned for marrying a white woman in 1957, although it was the start of a marvelous relationship that lasted 58 years until his death in 2015. And he was ridiculed for taking a stand against segregated games in the Jim Crow South as early as 1960.

As Flores said, Powell was ahead of his time — before John Carlos and Tommie Smith's gloved-hand demonstration at the 1968 Olympics and even before the 1967 Cleveland Summit of 12 leading African-American sports heroes, including Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali, Bill Russell and Lew Alcindor, who would become known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Powell himself believed his social stands would impact his sports legacy, but he did what he thought was right. Before passing in 2015, Powell said his only regret was that he may not have made a difference.

"There was a whole social movement going on at the time and it's way bigger than you," he said. "Art Powell didn't create those situations, and if he had never existed, those situations were still going to happen.

"I know I put my career on the line, and I know what happened in those years had an impact on how people looked upon me. So be it. It was my choice. The challenges that were before me were social challenges. They were personal and they were important. I chose to challenge them while others chose not to challenge them. I made a lot of people angry at the time, but I question if I made an impact.

"I've heard about African-American kids playing baseball who don't know who Jackie Robinson is. If that's the case, no one is going to know who Art Powell is."

So, we repeat: That is why Art Powell belongs in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. His historic accomplishments on the field, as well as off it, should be amplified, celebrated and remembered forever.